In nearly 19 years in search marketing, I’ve seen search marketers get cranky about a lot of things.

For a long time, the biggest pushback on something Google rolled out was the good old Enhanced Campaigns fiasco of 2013, when it essentially took away the ability to bid by device. (Google walked this back two to three years later at Google Marketing Live and acted like it was doing us a favor.)

That was the biggest pain in the butt…until Performance Max came along.

For those of you in the search marketing space who are as blind to reality as a NY Jets fan, Performance Max (aka PMax) is a new-ish ad unit rolled out by Google – and in beta testing with Bing, which I still refuse to call Microsoft Advertising.

You give the engine your money and a goal (say ecommerce orders or store visits), and it will cherry-pick all the platform’s ad units (Search, Shopping, Display, Video, Email, Maps) to work together toward a single KPI.

This sounds awesome until you want to get transparency on what placement is doing what, or the even more dreaded question: “What am I triggering for in search?”

Now, Google does claim that PMax doesn’t cannibalize ad placements – which means if you run Search, Shopping, or another ad unit in parallel with PMax, they won’t compete.

To be honest, I’m not sure I trust that claim. But I needed a test scenario to try and prove this out one way or the other.

Then, a client abruptly decided they wanted to cease PMax for a hot second, and boom – I had my test scenario.

Important Note: I am not a data scientist, and in no way is this a scientifically done analysis. These are purely surface-level insights.

Scenario

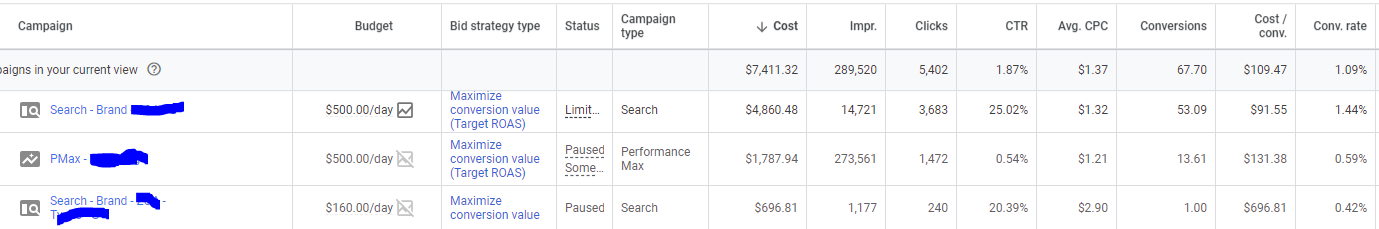

Prior to the brand wanting to pause PMax, we had consistently run brand search (Phrase and Exact match only) and PMax side by side.

Performance was often mixed; sometimes profitable, sometimes not. The results were typical for non-peak shopping season for their vertical.

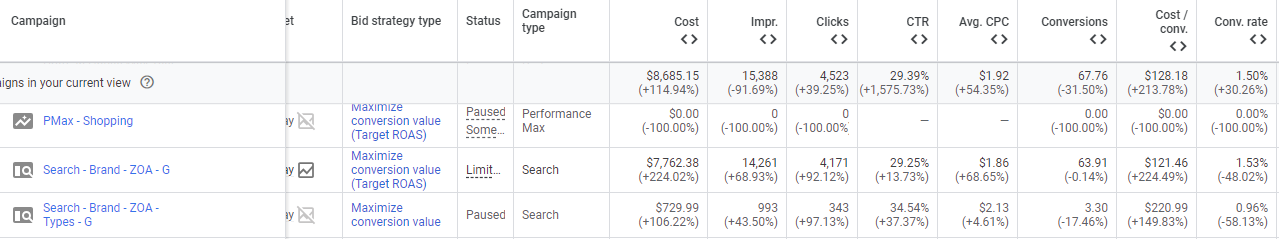

Screenshot by author, December 2023

Screenshot by author, December 2023

Bid strategies were always constant for them: PMax on target return on ad spend (TROAS), one search campaign on TROAS, and one on max conversion value.

These campaigns consistently chugged along – although prior to the brand making the call, there was a billing issue with the brand’s credit card, so the account went down for three days (a short period of time that shouldn’t impact the algorithms).

PMax would get pulled offline for eight days, but for the sake of sanity purposes, we analyzed seven days of it offline vs. seven days before it went offline and seven days after it came back online.

(Like I originally said, I’m not a data scientist, just a search marketer with a passion for bad reality TV and the NY Jets.)

Pre-PMax Offline Period

Looking at this seven-day period, we had come off of Labor Day weekend but were far enough away from it that traffic patterns came off as normal.

The three campaigns (two brand search and one PMax) had 185K impressions, with PMax driving 95% of them.

There had been 3.2K clicks (not doing “Interactions” for this, for the sake of continuity), with search driving 72% of them.

Spend was a little under $4,900, and the aggregate cost per click (CPC) was $1.24. The kicker is that the long tail brand search keywords had the highest CPC of them all (Google really said to hell with my QS on those).

We had 99 conversions, with 1/3 coming from PMax (not far off from the click and spend contribution percentages as well).

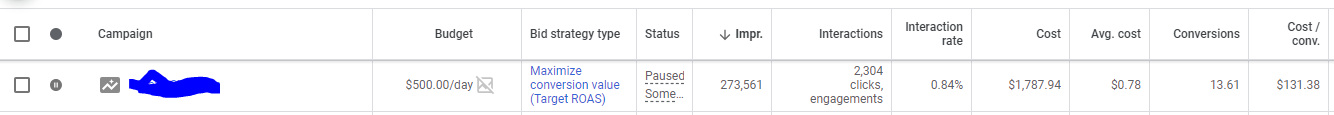

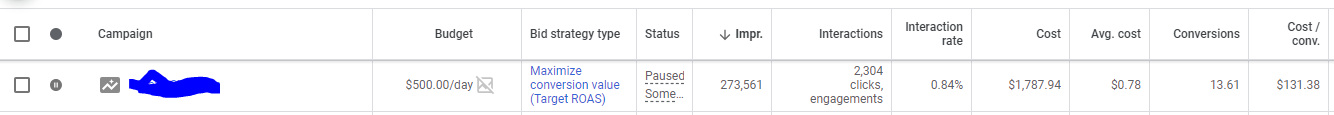

We ignore the impressions because PMax is going to blast all Google properties for impressions (for example, 3% of PMax impressions in this scenario came from TV screens).

But the conversion rate (CVR), clickthrough rate (CTR), and CPC will be the focus to decipher whether cannibalization/competition or not.

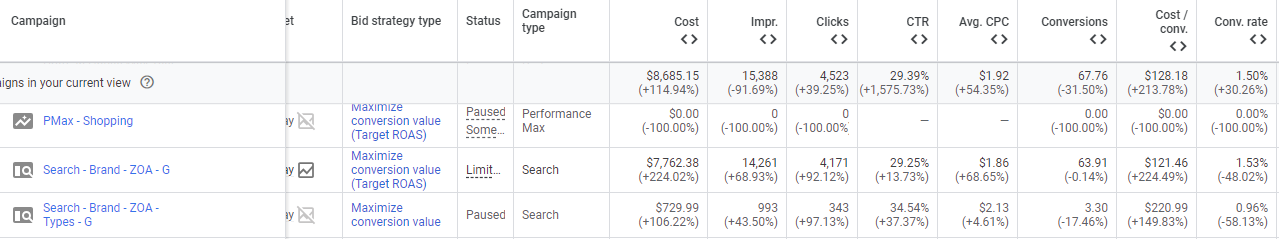

PMax Offline Period

During the seven days (out of eight) that PMax was offline and brand search was left to fend for itself, we observed some interesting data.

However, it should be noted the search bid strategy was not changed, but the funds used for PMax were reallocated back to search.

The shift in setup had an impact, but not quite in the way you’d expect. Search impressions rose 67%, but the aggregate impressions dropped 92%, as PMax wasn’t dumping the impressions anywhere.

In addition, search clicks rose 92%, but aggregate rose just 39% (remember this 39% growth, because here is where it gets a bit mind-boggling).

Spend, unencumbered by PMax stepping, for search rose a staggering 308%, but the aggregate was just up 119%.

Yes, a massive jump in spend from the reallocation (from PMax to branded search), allowing search to reach its full spend potential (within budget constraints), but just a 39% jump in clicks.

So why did this spend skyrocket? Well, the search CPCs grew 60%+ when PMax exited, driving the aggregate CPC up 51%.

On top of it, branded search impression share rose by 26%, impression share lost to budget dropped by 61%, and lastly impression share lost to rank dropped 24%.

Screenshot by author, December 2023

Screenshot by author, December 2023

Relaunch Of PMax

We reactivated PMax on the morning of the 9th day from when it was paused. Its budget, which had been reallocated back to search, was sent back, but no other changes were made.

We then evaluated the performance on week two of its relaunch (because PMax needs a week to relearn, so we tossed that out) and compared it to the PMax offline period.

Not surprisingly, in branded search, we saw an 11% drop in brand search impressions, a 23% drop in clicks, and a 24% drop in spend, but search CPC remained flat.

It should also be noted we saw a drop in impression share of 9%.

However, courtesy of PMax returning, aggregate impressions rose 35%, clicks 29%, and CPC dropped 7%. In addition, we saw a 91% increase in conversions.

What Does This Mean?

So, with spend wavering, despite even reallocation of the aggregate budget back into brand search and then back into PMax, the data gets fuzzy. But we note the following:

- Brand search CPC is at its highest cost when it is solo (vs that of brand search and PMax).

- Brand search CTR is higher when PMax is offline.

- Brand search CVR is lower when PMax is on.

- There is an exchange of click volume between PMax and brand search when PMax is on vs. off.

PMax has a clear and definitive impact on brand search when it is on vs. when it is off.

The Takeaway

How Google defines “does not compete with paid search” (brand specifically here) when they are run together is a bit suspect. As the loss/gain volume of clicks is a dead giveaway, there is an immediate impact.

But at the same time, running them dually shows an aggregate net impact, positively for CVR and CPC.

Providing the positive impact of CPC is for brand search, and PMax’s CPC is equal to or lower than the share of clicks it takes from brand search, then who cares?

I will wholeheartedly admit that I have had a bias against Performance Max since its inception (and I still do).

I also expected to walk away from this analysis and say that PMax is evil and destroying the value of brand paid search when they run together. But I may be wrong.

When we look at them in tandem, we see a lower aggregate CPC, and search has only a slight dip in CVR, but total conversions increase.

This means we see a holistic bonus/positive directional growth when they run side by side.

My (personal) stance is: Yes, PMax is cannibalizing/competing with paid search, but if it continues to produce holistically better search performance, then I am down for that.

I encourage others to test things out and even do the brand exclusion test on PMax, as that is likely a cleaner way of doing this type of analysis.

Needless to say, the outcome of this analysis was as humbling and surprising as when I elected to remove clogged ice from my snowblower (when I thought it was off) in 2020.

I learned a valuable lesson the hard way.

More resources:

Featured Image: eamesBot/Shutterstock